Is Time a Part of the Universe?

In a previous post “Why the Cosmological Argument Fails – Part 2” refuting the premises of the cosmological argument I argued that the premises did not hold because time is a part of the universe. This means that temporal concepts such as “beginning” cannot sensibly be applied to the universe.

In the comments section I was asked to expand a bit on this reasoning, and ended up writing quite a bit about it (thanks essiep!). I wrote so much that I decided the topic deserved to have its own article, so here we are.

Four-Dimensionalism

There’s a debate in metaphysics over whether developments in physics suggest that we should talk about objects as if they were four-dimensional instead of three dimensional. To convey the picture, the you at this precise moment is just a “temporal part” of the real you. You’re not a 3D object really, you’re a spacetime worm made up of the 3D yous as slices and extending into the fourth dimension time.

It turns out that talking about objects like this yields some nice solutions to long-standing philosophical paradoxes in persistence. Like anything in philosophy however, the nice resolutions to some problems are counterbalanced by problems in other areas. The key objection to four-dimensionalism being the intuitive one; that we seem to undeniably be 3D objects, not 4D ones. It’s still a task for the four-dimensionalist to show why it is we appear to be 3D if actually we are 4D objects.

The Four-Dimensional Universe

It should be clearer now why I say that the universe contains time and not the other way around. If you look at the universe from a four-dimensional perspective, the universe is the entirety of space and time. The universe is not just everything that is, it’s also everything that was and everything that will be. If the universe is the entirety of spacetime then it contains time in its entirety too.

We can say the universe has “temporal parts”. The 3D universe at this current moment from your perspective is a slice of the whole of 4D spacetime, it is not the entirety of the universe. But here you may object – what if I want to call the 3D universe “the universe”, not the 4D object. This is the position of the three-dimensionalist or stage theorist.

At this point it may seem a matter of preference. Are you okay with calling 4D things objects? Or do you think this is an affront to reason and that we should only ever think about calling 3D things objects? Neither lead to philosophical contradictions, does this argument even matter, or is it just a linguistic argument?

I argue that the evidence is in our physical theories that the universe has to be considered as a 4D, not a 3D object.

Relativity

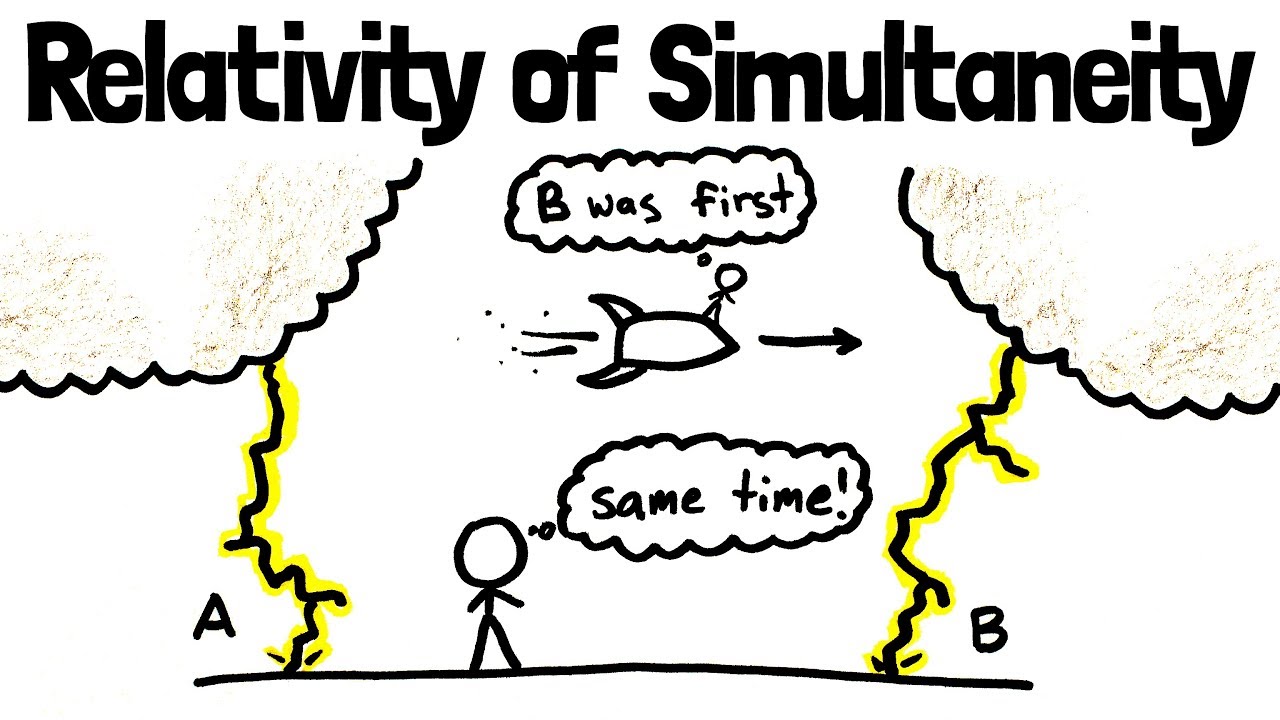

One of the most profound concepts in relativity is that simultaneity is relative. The notion of things happening at “the same time” is relative to how fast you are moving. From my perspective a star may explode just as I open the door to my rocket. You on the other hand zooming past me will see the two events occur at different times. I’ll open my rocket door after the star explodes from your perspective.

What this shows us about the world is that there is no notion of “global time”. There’s no giant clock sitting external to the universe using which you can say objectively whether two event happen at the same time or not. Time is something that only makes sense in the way we commonly think of it from the perspective of a single inertial frame.

This shows clearly to me that time has to be considered a part of the universe. If three-dimensionalism were valid when applied to the universe, you would be able to stop the universal clock and count all the existing objects at a particular time in the universe. But you can’t do this objectively.

Suppose I stop my clock and make a log of all the objects I observe to exist in the universe. Say you’re travelling at a constant speed relative to me and we decide to simultaneously stop our clocks and make a log of what existed from our perspective in the universe. If we were to restart the clocks and compare our notes we’d find that our lists would be different. We would disagree over which objects existed in the universe at the time we stopped the clocks.

Three-Dimensionalism Cannot Make Sense of Relativity

It is worth mentioning that there is a caveat here, although there is no objective way of assigning a global time to the universe, this doesn’t mean it’s not possible. It is possible to slice up the universe into time slices and then call that a “global time”, but the point is that there is no unique way of doing it.

If this global time did exist it would violate a postulate of relativity that there are no special inertial frames. If global time did exist then there is a special frame in which you would experience that true global time, but there is no evidence that this special frame exists and it actually contradicts special relativity.

It may still be alright to talk about everyday objects as being 3D, because everyday objects don’t move that fast relative to each other and we can approximate the situation with a global time.

But when it comes to the universe we have to treat it as a 4D object, if we didn’t then we would be able to pick out a special inertial frame and a “global time”, but there is no empirical evidence that we can do this.

This is why I say that the universe must contain time. The universe is best thought of as a static 4-dimensional shape of which slices are all we can perceive. What really bites is that we all perceive different slices of this 4-dimensional shape, and how would that be possible if the universe were only 3D?

Back to the Cosmological Argument

With regards to just the cosmological argument however, it really doesn’t matter to my criticism whether the universe is in fact 3D or 4D. An argument can be made that the universe has no beginning even if we treat it as 3D:

Now perhaps you can argue that I’m being unfair here and that what we mean by the universe is a particular slice of spacetime (i.e. a 3D slice of the universe at a particular time), not the aggregate of all these slices. I maintain that this is problematic because there is no “universal time”. Relativity means that simultaneity is relative and we can’t define a global time for everyone in the universe. But let’s ignore this difficulty for now and say that I have to deal with a 3D slice. Fine. Now we can embed these slices, and so the universe, in time. The universe around you at the moment is a 3D slice and we’ll give it a time-stamp of 8pm 12th December 2018 or whatever. The universe is now embedded in time.

This still doesn’t mean the universe has a beginning though, because we run into a problem. The universe may be embedded in time now, but we can’t point to a time at which the universe did not exist (which as you’ll recall is my definition of began).

We can get to the moment of the Big Bang, but this is our first time, we can’t go any further back in time than this moment. But the universe existed at this moment. So at every time you can possibly point out: now, 5 minute in the past, 10 billion years in the past, the universe existed then. If you could find a time before the Big Bang then there would be a problem because the universe comes into existence with the Big Bang, but you can’t say “before the Big Bang” because the Big Bang is by definition the first moment in time, there is no time before it.

So it is not true that the universe began because there is no moment we can point to at which the universe did not exist.

It may sound strange to say that the universe has always existed, but it has a finite age, but this is the way it is. The universe has always existed because it there is no time at which it didn’t. There’s just a finite amount of time, hence why the universe can be said to have an age.

In any case I have very little doubt in my contention, based on current physics and philosophy, that the universe had no beginning. I’m also quite firm that the universe must be seen as a 4-dimensional object, but given the persuasiveness of the illusion that objects around us are 3D, there is some doubt there.

Interestingly, regardless of whether one subscribes to a Tensed model of Time (what you’ve called a 3-Dimensionalist view) or a Tenseless model (your 4-Dimensionalist view), the classical position of philosophers for at least a dozen centuries has been that Time is a physical thing– and therefore, a part of the physical universe. Even such a venerable theologian as Augustine of Hippo, in the 4th Century CE, held to such a view.

This is a large part of the reason that Classical Theology holds to the belief that God must be literally timeless.

So, regardless of whether one is a 3-Dimensionalist or a 4-Dimensionalist, as you’ve termed them, it is still incoherent the ask what there was before the physical universe, because there’s no such thing as “before” Time. It must still be the case that the universe was never non-existent.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Your contention that the universe has no beginning seems to be based on the fact that time can be considered part of the universe, so that it makes no sense to ask what happened “before” the big bang.

Isn’t this like trying to prove that the south pole doesn’t exist because it doesn’t make sense to ask what is south of the south pole? You can’t go further south than the south pole, but the south pole is still there. You can’t go further back in time than the initial cosmological singularity, but you still reach this limit state that cannot have a physical explanation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A thoughtful question there!

Both the south pole and the Big Bang singularity exist, they are both points defined by special properties. The south pole is the point on the earth at which you can no longer travel south. Analogously, the Big Bang singularity is the point at which you can no longer travel backwards in time.

My contention is not that the Big Bang singularity doesn’t exist, but that it is incorrect to call it a “beginning” because there is no time before the Big Bang and hence no time at which the universe did not exist.

As to your last point you do reach this limit state, I say that this limit state doesn’t need a cause because it’s not a beginning. As to whether this point can have a physical explanation, yes this is a tricky problem to address. I don’t think we have a right to say that it absolutely cannot have a physical explanation. For a start we have no idea what this limit state could’ve been, our physics is not advanced enough yet, so it’s hasty to claim it can have no explanation when we know nothing about it.

Furthermore, the universe seems not to agree with our view that everything requires an explanation. Radioactive decay for instance is constrained by probability laws, but the actual event of decay is totally unpredictable. It seems to be a physical event without explanation. Perhaps this is because our physics is not advanced enough yet, but I think this teaches us a valuable lesson. The universe is reality and how it behaves should inform our intuitions and not the other way around. The universe seems to disagree with our intuition that everything requires an explanation, and this should make us very wary about saying things like “this limit state cannot have a physical explanation”- maybe it doesn’t need one.

LikeLike

Radio active decay is a random process that obeys chance , and chance does seem to play a part in quantum physics. It is very curious that randomness ( I’m not too sure what that is) obeys a law in this case. There is much debate today about the chance of self replicating molecules forming since that is essential to kick off natural selection. Richard Dawkins discusses it at length in his book The Blind Watchmaker . It’s a good book but I found the mathematics a bit daunting having no higher education.

LikeLike

So, you claim that a _necessary_ condition of an event being a beginning is that there is time _before_ that event. Why? Why isn’t it enough just to be the first moment of something’s existence, whether or not there was any time before that moment?

LikeLike

It’s a neat way of slipping out of the problem of having a beginning to the universe since it must exist in time. Many years ago( I’m 76) my father used to sit and listen to James Jeans on the wireless , old dad always had a fascination for such stuff . Jeans had a theory of continuous creation , a sort of something for nothing , he believed material was being created all the time and so there was no beginning and no end.

Newtonian time is part of our very make up and all our bodily processes seem to take place in Newtonian time . Even if we were on a spaceship travelling at half the speed of light we would still age and die .

There was a young lady called White

Who could travel much faster than light

She set off one day , in a relative way

And returned on the previous night.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Time symmetry is such a strange bird. In 2011 in a New Orleans high school geometry class, we unwittingly started exploring it through embedded geometries: http://81018.com/home/ We went further and further inside a simple tetrahedron by dividing the edges by 2 and connecting the new vertices. In 45 steps we were in the range of CERN labs measurements. Within another 67 steps we were in the range of the Planck scale. When we multiplied our little tetrahedron by 2, in 90 steps we were out somewhere around the observable universe. Just over 202 steps, we had a simple, mathematical model of the universe by applying base-2 notation. We call that process, doublings, or the power of 2. It became our STEM tool. But it also gave us about 64 notations or doublings that were clearly below our thresholds of measurement. The most current wrestlings with it all are here: http://81018.com/planck-scale/ It all suggests that every notation is always actively supporting and engaged with all others and that the Now is the only time. But, within a given notation, there could readily be a sense of time. Symmetry on one hand and asymmetry on the other. We are struggling with it all. -Bruce

LikeLike